Disclaimer:

Please be aware that the content herein is comprised of personal reflections, observations, and insights from our contributors. It is not necessarily exhaustive or authoritative, but rather reflects individual perspectives. While we aim for accuracy, we cannot guarantee the completeness or up-to-date nature of the content.

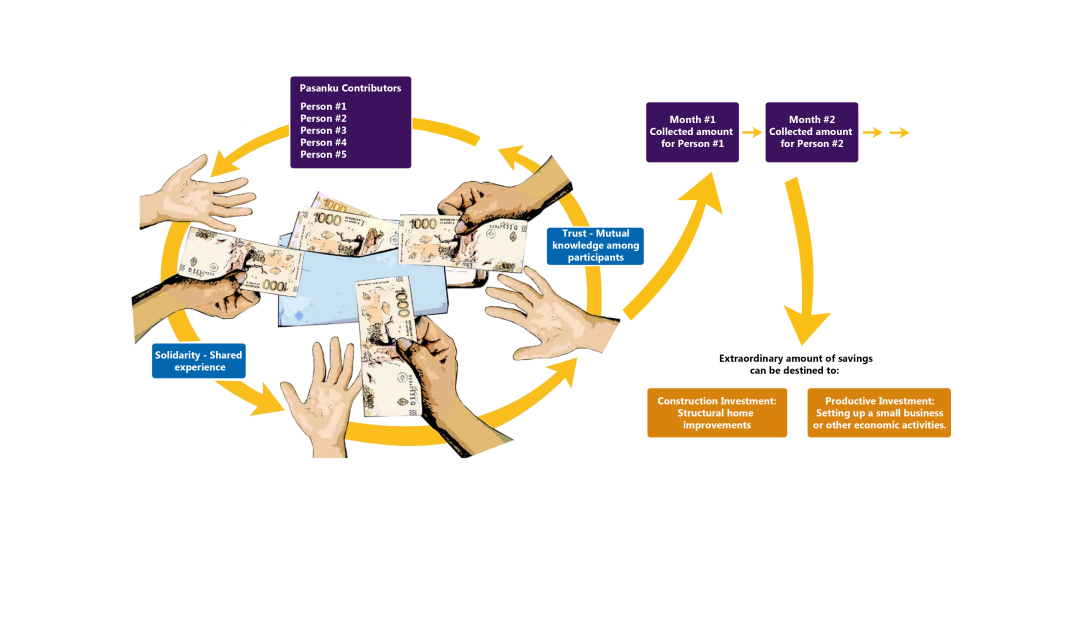

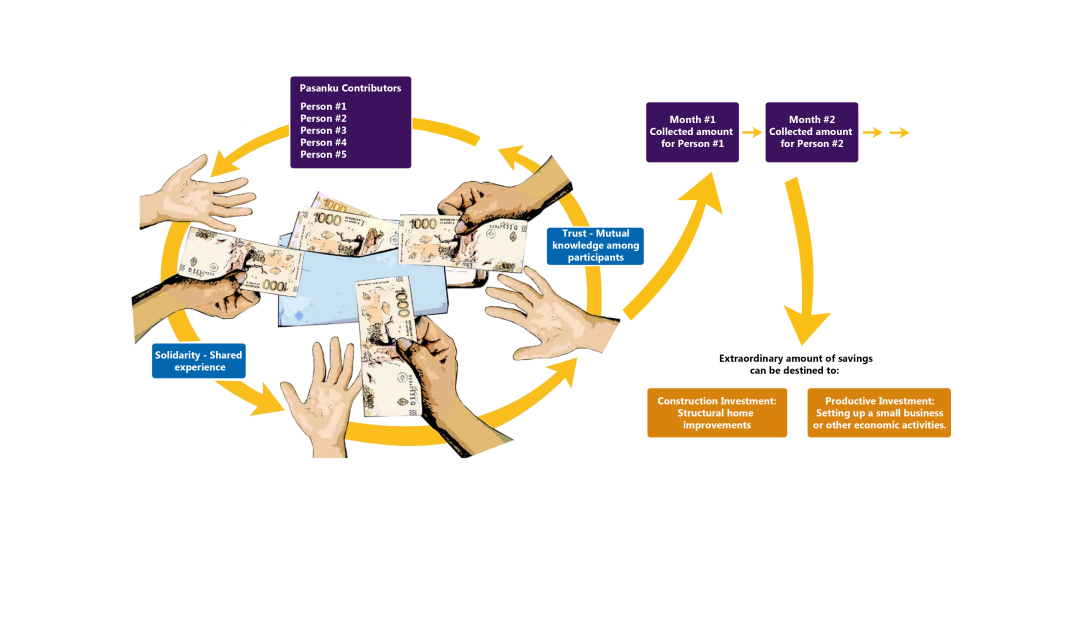

Difficulty in accessing different financial services is a historical problem for low-income sectors. Overall, households have a low level of financial soundness and their access to the labor market—mostly precarious and/or temporary—means they are mostly in the informal sector of the economy. This makes them extremely vulnerable to macroeconomic changes, emergencies, or unforeseen events. In this context, interpersonal agreements based on trust and closeness gain relevance. Family and/or community credit wheels—also known as Pasanakus—are structured within the neighborhoods and may be made up of small groups or a larger number of people, as long as participants know each other. Based on an individual monetary contribution agreed by the members, a common fund of money is consolidated and its distribution can take two forms: i) simultaneous request for money or ii) the chronological order in which the money is received, given at random or according to the members’ needs. In the case of Pasanakus, there is usually a monthly contribution, and the total amount is systematically drawn among members. Participants take turns to receive the money on a monthly basis until, finally, all the members of the group have received the total amount of contributions. One of the members takes up the role of organizer, as someone is needed to collect payments and distribute the gathered amount; this person tends to receive the first sum as a benefit for their work. Access to financing—at all levels—represents a widespread tool within low-income populations and a strategy to create solidarity finance in response to the absence of traditional financial services adapted to low-income populations. This implies the democratization of financial resources at the service of the community since it allows access to the necessary economic resources for livelihood and economic activities. This solution stood out, particularly, during our gender mapping, where we focused on financial inclusion solutions through a gender lens. The interviewed women shed light on the Pasanaku circle: “One of the boys that I told you about, his parents play Pasanaku, (…). One family puts in two thousand pesos, another family puts in two thousand pesos and the other one puts two thousand pesos. After they all put the two thousand, they draw a number and, during that month, the [REDACTED] family gets all the money. After that, they draw another number and it's like they're rotating. It's like the money rotates, it doesn't stay there. So, when someone else needs money to build their house (...), they play that game, which is a profitable game, because the money goes around, it is not that they are losing, your number is always going to come out, the thing is that it rotates.” Interview #21 young woman from “Mujeres en red: soluciones financieras y de recuperación socioeconómica” (Women in Network: Financial and Socioeconomic Recovery Solutions). Community finances are a space for savings and access to money within the neighborhoods that are based on a verbal agreement among participants. Part of their successful operation and long-term continuity has to do with the fact that they are built on trust, based on mutual knowledge among participants, and solidarity, as a result of the understanding from sharing the same situation or having experienced it at some point in time. Participants are all equally interested in generating this amount of savings that otherwise would have been out of their reach without the intermediation of financial institutions or moneylenders. Indirectly, the Pasanaku allows to reach savings that could be destined for bigger projects in terms of time, effort, and results, such as structural home improvements, setting up small businesses, or other economic activities. Finally, we should note that solutions like the Pasanaku or credit wheel become less efficient in an inflationary context, as they operate with non-indexed amounts. Nevertheless, only a few interviewees recognized this problem, and, despite this, they use this solution because of the previously mentioned reasons. What it’s clear is that inflation represents a clear obstacle to savings-generating solutions.

https://www.undp.org/es/argentina/publications/mujeres-en-red-soluciones-financieras-y-de-recuperacion-socioeconomica<div><br></div> https://www.undp.org/es/argentina/publications/busqueda-compartida-mapeo-de-soluciones-colaborativo-inclusion-financiera-y-recuperacion-economica

https://www.undp.org/es/argentina/publications/de-cerca-inclusion-financiera-y-soluciones-territoriales

Consent to share form or official link.

Consent to share form or official link.

1No poverty

1No poverty 8Decent work and economic growth

8Decent work and economic growth 10Reduced inequalities

10Reduced inequalities 17Partnerships for the goals

17Partnerships for the goals

Comments

Log in to add a comment or reply.